A study by a team of researchers in Japan wanted to conclude whether addictive behavior stems from nature or nurture – do bad choices occur because of pre-existing conditions, or does habitual drug use cause altered decision-making patterns. So they took a bunch of mice and got some of them addicted to methamphetamine. Some of the mice, known as a control group, received a saline solution instead. Then they built them a casino with “slot machines” and tested the animals over a period of time. The results of their study were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The slot machines consisted of four arms. One arm was set as low-risk/low-reward (L-L), giving lots of little wins, like Derby Dollars from RTG. The rats got a single food pellet 14 times out of every 16 “spins”. The other two turns gave them a nasty tasting quinine pellet. On the other end of the spectrum was an arm set as high-risk/high reward (H-H). Pulling this arm gave the rats seven yummy food pellets when it paid out nice, which was only twice in every sixteen spins. 14 times out of every 16 the poor fellows got the bitter pill. Sound familiar? This slot was like a highly volatile game such as Dead or Alive from NetEnt – great when it’s good, but leaves a bitter taste in your mouth most times.

The two arms in between offered nothing, no win, no loss, no food, no quinine.

The meth addicted rats chose the high variance machine more frequently than their non-drugged casino floor mates. They also returned to that choice in subsequent trials, even though they were going to have a bad experience seven out of every eight attempts. Perhaps most interesting though is that when they got a bitter pill playing the low variance slot they immediately switched to the high risk machine far more frequently than the control group rodents.

The study concluded that drug-addled rats assign higher motivational values to large rewards.

We conclude that the return to player percentages (RTP) were consistent, so it must have been a fair game. Although we caution readers not to try this at home.

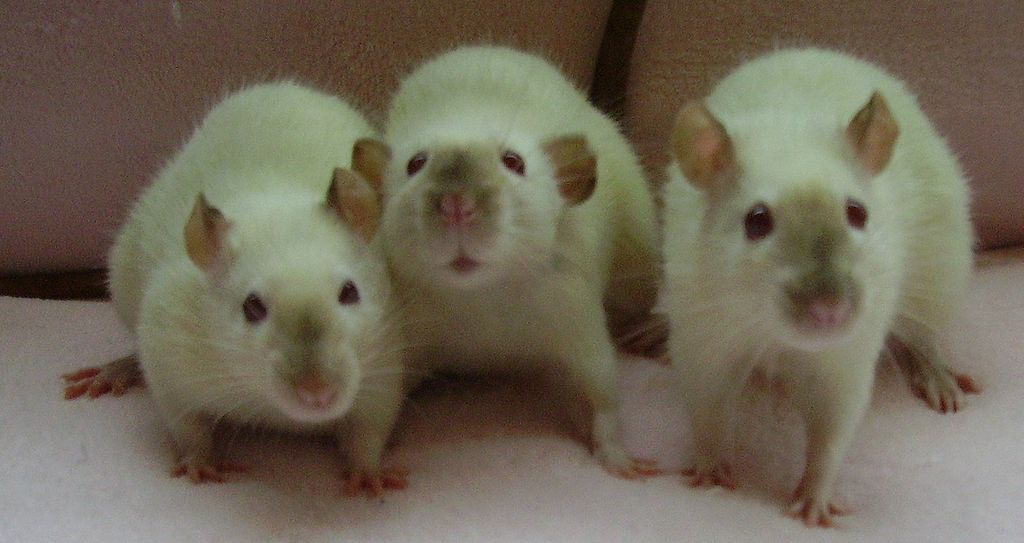

Update: Editors apology. No mice were harmed in this study as only rats were used. We understand that “mice”and “rats” are not interchangeable and apologize if anyone was offended. Only about 90% of rat genes have counterparts in the mouse and human genomes. Mice are mice and rats are rats.