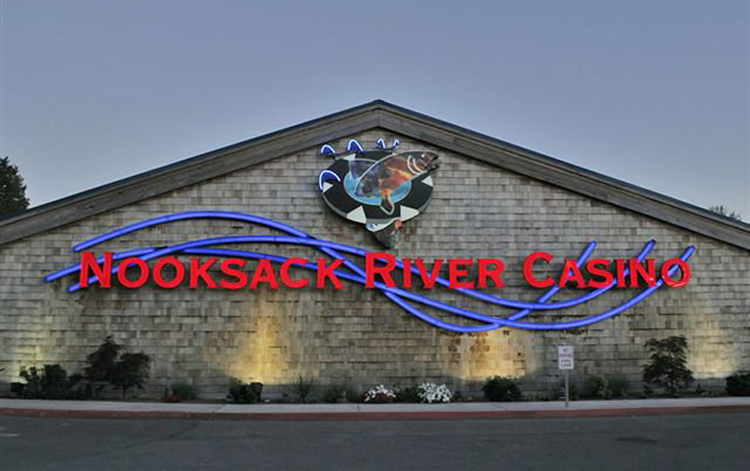

Whether or not money made in the future from the building currently housing the Nooksack River Casino belongs to a company attempting to collect millions of dollars the casino owes in unpaid loans, will soon be decided by a Whatcom County judge.

On Friday, December 18, loan servicing company, Outsource Services Management, and attorneys for the Nooksack Business Corporation, owned by the Nooksack Indian Tribe, met before Superior Court Judge Deborra Garrett. Arguments centered on whether Outsource would be entitled to any revenue generated from non-casino activities in the building since the casino in Deming, Washington was abruptly shuttered last week. Outsource contends that it would be entitled to collect on the more than $20.7 million in loans and fees if the building is converted to any business other than a casino. The tribal entity disagrees with the money collected being used to re-pay the loan under a portion of Outsource’s contract with Nooksack.

Nooksack’s lawyer, Connie Sue Martin, argued that because the building is on property held in trust for the Nooksack tribe by the U.S government, imposing an order against it would violate federal law. While Judge Garrett said a decision would not be made until Martin’s new argument was heard, she did say that she was leaning more towards the “broader definition” presented by Jerry Miranowski, Outsource’s lawyer, according to the Bellingham Herald. If possible, a decision on the case is expected by Wednesday, December 23, or the following week.

In the interim dozens of casino employees who abruptly found themselves jobless when the casino was closed on Friday, December 11, are left wondering what to do next and trying to decipher the situation. The closing happened so fast and with so little notice that some of the approximately 125 employees were not aware until they arrived for their shift on Friday evening and found the doors locked. Allen Mullen, a 62-year –old table game dealer was one of those employees. Mullen said no one mentioned the casino would be closing when he left work on Thursday evening after his shift. He said that upon arrival for his shift on Friday he was led into the employee break room where a woman he did not recognize asked for his tribal badge and informed him the casino was closed.

Mullen said he had many questions to ask including what would happen to his insurance coverage. That question was answered when Mullen attempted to fill a prescription and was told that his insurance had lapsed on December 11, and when Lisa Henkel, a fellow employee, was told her insurance card was no longer valid at a doctor’s appointment. Both employees said that months earlier they were told that the casino might close, but were never told anything was definite.